Action to Thought to Action, 1927

Initially published under the pseudonym of Patrick Durrell, this philosophical pamphlet is considered a futile and pretentious exercise by the Burnsteins’s detractors. It contains the nucleus of the Hungarian scientist’s comportamental theories and a first definition of ‘empathology’.

Soup Without Salt: Three critiques of poverty and the individual’s responsibility, 1930

This passionate, disjointed book – clearly influenced by Marxist thought – was born as a series of notes destined to become the theoretical corpus of the Tambov rebellion. It represents the attempt of an idealist, twenty year old Burnsteins to intervene in economic and political debate of the time, prefiguring an alternative path to communism.

Mechanisms of Consciousness, 1931

Written with his college friend Randolph Brown, Mechanisms of Consciousness reports on a series of experiments conducted at Oxford about the cognitive capacities of man. In the final chapter, Burnsteins and Brown put forward the theory of ‘communal reactions’ between man and animal, thus opening the theoretical route towards the idea of ‘manimality’.

Insight Through Ignorance, 1935

An early work, fairly independent from the Burnsteins’ more well known system of thought. Insight through ignorance – utilising suspect statistics – supports the hypothesis that unschooled minds have access to a bigger share of knowledge, put simply this research proffers that education limits our intellectual potential.

The Pre-Human Condition, 1941

Burnsteins states that The Pre-Human Condition is his ‘critique of pure reason’, Intended to be the first of a series of three about the ‘cycle of needs’. In this pamphlet Burnsteins maps out the primary requirements of all animal’s , the fulfilment of which leads to the human condition.

The Post-Human Condition, 1946

Burnsteins described this, the second volume of his cycle of needs as his “critique of practical reason”. Having described the pre-human condition, Burnsteins moved directly to the post-human condition, describing human beings that, once having reached the peak of “power status”, would revert back to more animalistic behaviours. The human condition, the third volume of the Cycle of needs, never can to fruition.

He Who No's, 1961

Obsessed by the thought of dying, Burnsteins wrote this early autobiography when he was only 50, presenting himself as a virtuous scientist who had always defended the ‘human condition’, rejecting the academic world as well as ‘powers caprices’. The book was ridiculed by most critics of the time.

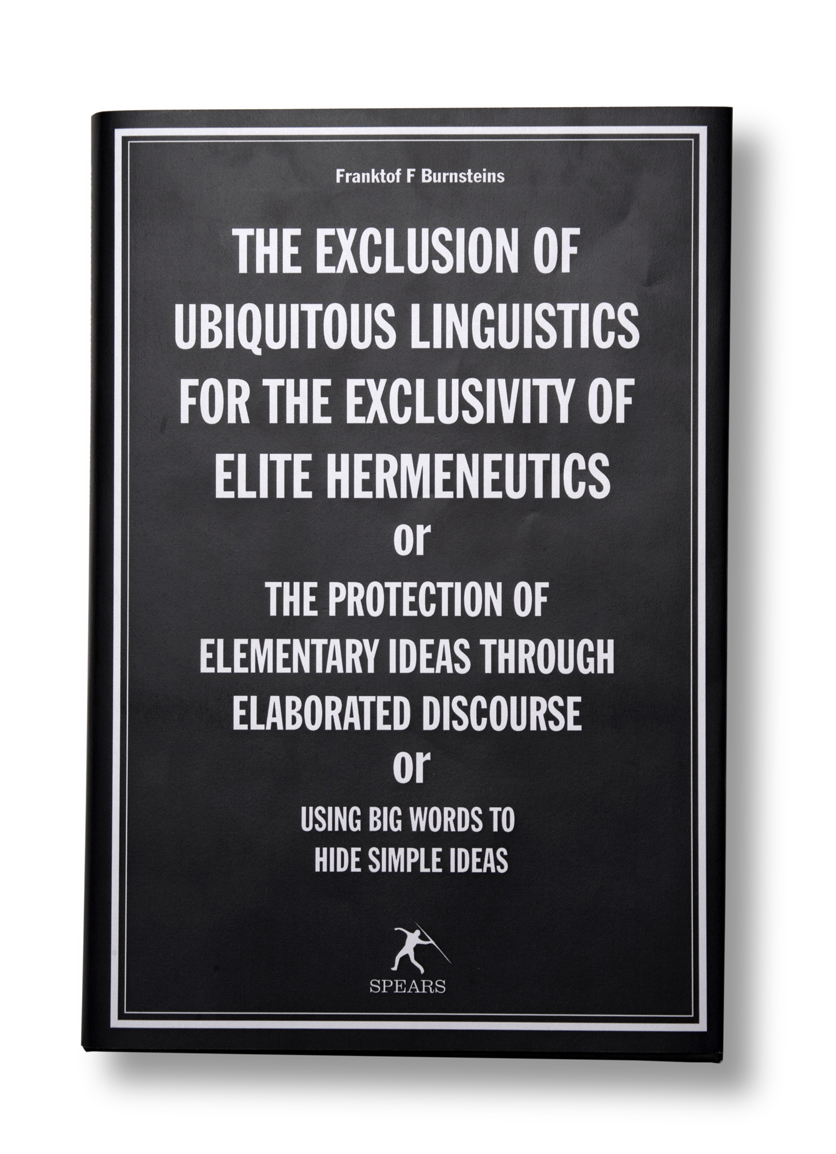

The Exclusion of Ubiquitous Linguistics, 1962

Disappointed by his professional failure within the academic world, Burnsteins condemned, in this volume, the habit – widespread amongst university professors – of protecting the nature of ideas by dressing them up in incomprehensible language. It’s a book dictated by rage more than by reasoning, and yet in the 60s it became a bible of dissident student movements across Europe.

Apokolips Fatigue, 1968

In a time of action – the Vietnam War is at its height and riots and revolutions are shaking the Western world – Burnsteins writes a bleak book: Apocalypse Fatigue is a collection of aphorisms on the fast approaching nuclear apocalypse and on how human beings are paralysed by the idea of the end of the world.

Foodbourne Amnesia, 1971

This book was written at the beginning of the 40s on the Galapagos Islands and contains both Burnsteins’ theories on food and an open critique of Darwin and his followers. After showing that man is vegetarian by nature, Burnsteins savages the carnivorous naturalists, putting forward the hypothesis of an ‘independent evolution’.

Social Cannibalism, 1972

This illustrated book describes the creative process not as the isolated product of a genius mind, but as the ingestion and reappropriation of concepts that were previously introjected. This ‘received knowledge’ or ‘cannibalistic knowledge’ theory is an essential piece in Burnsteins’ theory of ‘relative truth’.

Absolute Truth and Other Possibilities, 1973

Although muddled and apparently inconsistent, Absolute truth and other possibilities summarizes the whole of Burnsteins’ epistemological thought. In these pages the Hungarian scientist restates that truth is necessarily subjective, opposes again the ‘complete theories’ and sets up a goal he would never be able to reach: the construction of a humanism meant to be ‘truly for everybody’.

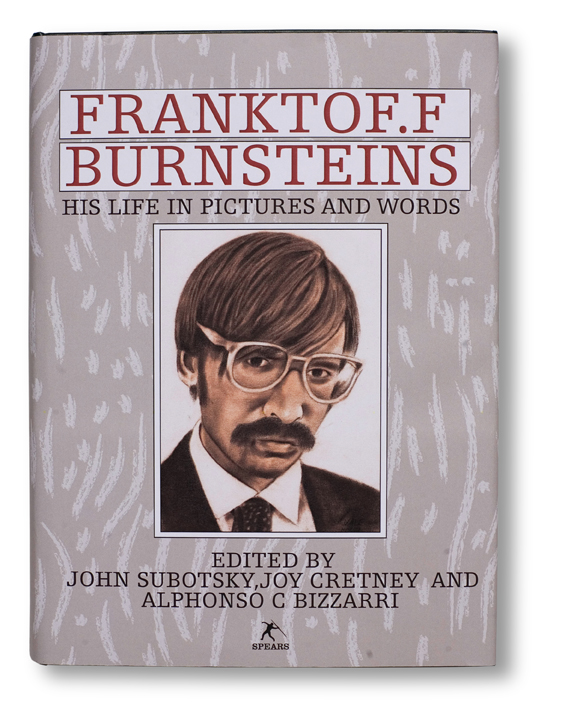

His Life in Pictures and Words, 1987 (Reprinted in 2000)

The last of Burnsteins’ volumes, published posthumously and compiled by his closest collaborators. Conceived to be the Hungarian scientist’s definitive body of work, it failed in its intention. Still, the book contains a complete biography of the author, enriched by both unpublished photographic material and theoretical writings this volume does pave the way for new interpretations of one of the 20th century’s most eclectic minds.