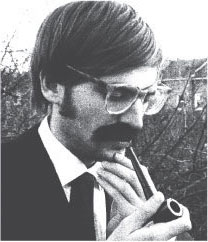

The Life of FF Burnstein

Franktof F. Bernsteins (1902–2001)

Not everything misunderstood is profound. But Franktof F. Bernsteins made a career, perhaps even a life out of the chance that it might be.

Born in 1902 in Kőszeg, Hungary, Bernsteins came into the world with two immediate disadvantages: illegitimacy and curiosity. The former cast a long shadow over his sense of belonging; the latter ensured he would spend the rest of his life examining the outlines of the shadow. His mother, a teenager from Alsace, vanished from his life early. His father, a peripatetic physician with vague affiliations to half a dozen crumbling empires, took him across Central Europe like a stowaway idea looking for a thinker.

There is a possibly apocryphal family story that as a child, Bernsteins briefly stayed with Hermann Ebbinghaus. If true, the experience left no trace on Ebbinghaus, and only a vague one on Franktof, who claimed later in life to have “forgotten everything about memory.” He did, however, spend formative years in Mulhouse with his mother’s family, and may have been a subject in Alfred Binet’s early educational tests. “They asked me what this was,” he wrote under one of his later diagrams. “I didn’t know then either.”

He moved to England after the First World War, having survived the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, several governments, and a mistranslation that nearly saw him sent to the wrong country—and enrolled at the University of London. There he studied under Bernard Bosanquet, who believed that philosophy should reveal coherence. Bernsteins, characteristically, suspected it should instead reveal interference. His thinking bent toward the perverse, though rarely the self-serving. Through the South African-born idealist Alfred Hoernlé, Bernsteins took up an unofficial research post in Johannesburg and began working with Dr. Friedrich Keller on a long-form study of symbolic reasoning in children.

The study was published in 1938. His name was not on it. He discovered this in London, in the living room of a friend, holding the English edition of the book. The publisher claimed a mistake in the translation; others whispered antisemitism, academic politics, or the small, persistent fact that Bernsteins had no formal credentials in South Africa. He said nothing, and began instead to think about what authorship really meant.

It would be one of his most enduring questions.

His brief stint with Cyril Burt’s twin studies ended even less nobly. Bernsteins either noticed or fabricated inconsistencies in the data, and raised the matter discreetly, which in academic terms meant with

catastrophic consequences. He was ejected, and for reasons of reputation, temperament, or sheer bad luck, never again held a formal academic post. Instead, he founded The Institute for Comparative Symbol Systems: a name so cumbersome it ensured no one could accuse it of being a cult, though a cult is what it occasionally became.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, the Institute moved between borrowed buildings and borrowed ideas. The tools it produced, most notoriously the BIAS Scale and the Mirror Box Interviews, were either brilliant provocations or elaborate forms of nonsense, depending on who was using them. Bernsteins’ central claim, never quite stated but often implied, was that testing was a kind of performance art, and performance art a kind of test.

By the early 1970s, Bernsteins had followers, enemies, and a lecture circuit. He was accused of authoritarianism by the communes he helped inspire, and plagiarism by scholars whose work he had apparently misread into originality. Asked about his debt to Korzybski, he once replied: “He came to it through reason. I arrived through failure. Let him keep the map. I got here by accident.”

Disillusioned but undeterred, he retreated to the English countryside in the 1980s, where he lived in semi subsistence, growing vegetables and pursuing what he called “subsistence experiments”—quiet investigations into whether patterns of awareness might emerge in plant life

He died in 2001. A small group of former students and collaborators scattered his ashes in the field behind his cottage, where he had once attempted to observe plant cognition using only mirrors and sunlight.

His legacy remains unsettled, elusive, and difficult to categorise. As if by design.